When you spend most of your time and attention, mired in the day-to-day world of Chain of Custody (CoC) certification, it can be easy to lose sight of why we work so hard at all of this. At MixedWood, we are fond of pointing out just how much the FSC, SFI, and PEFC programs have in common. One obvious but often overlooked point is in their names. In our modern world of acronyms and abbreviations, our favorite “green” certification programs are most generally referred to by their initials. Not Forest Stewardship Council, but FSC. Same for SFI & PEFC. Have you ever noticed that these programs only share one initial in common? Not accidentally, that’s “F” for Forest. Something to think about.

When you spend most of your time and attention, mired in the day-to-day world of Chain of Custody (CoC) certification, it can be easy to lose sight of why we work so hard at all of this. At MixedWood, we are fond of pointing out just how much the FSC, SFI, and PEFC programs have in common. One obvious but often overlooked point is in their names. In our modern world of acronyms and abbreviations, our favorite “green” certification programs are most generally referred to by their initials. Not Forest Stewardship Council, but FSC. Same for SFI & PEFC. Have you ever noticed that these programs only share one initial in common? Not accidentally, that’s “F” for Forest. Something to think about.

It can be exceedingly difficult to maintain our focus on Forests and Trees while we manage the daily business challenges of producing, selling, buying, and auditing certified wood or paper products. One excuse we have is that so many of our products don’t look anything like a tree. A good example is the hamburger box that we featured in our blogpost in late January. Our short article called attention to the importance of a major consumer product company like MacDonald’s making a decision to  source FSC-branded products for its enormous quantities of paper products. Beyond using a label containing the letter F, there isn’t much reason for a hungry MacDonald’s customer to think about sustainable forestry though, is there? This broadly true for most paper-based products. We know, intellectually, that paper is made from trees, but that’s about all we know. And if we can’t see the trees, how can we possibly see the forest?

source FSC-branded products for its enormous quantities of paper products. Beyond using a label containing the letter F, there isn’t much reason for a hungry MacDonald’s customer to think about sustainable forestry though, is there? This broadly true for most paper-based products. We know, intellectually, that paper is made from trees, but that’s about all we know. And if we can’t see the trees, how can we possibly see the forest?

At the lumber yard

Fortunately, there are consumer products for sale – with FSC and SFI brands – that give us a good look at the trees that they come from. Solid wood products, like lumber, are a relatively small portion of the certified market, but they are still a big deal. They are not that hard to find, and they sometimes tell an interesting story. Here is a look at how many American’s buy their lumber in the self-service aisles of a major, do-it-yourself home center.

Fortunately, there are consumer products for sale – with FSC and SFI brands – that give us a good look at the trees that they come from. Solid wood products, like lumber, are a relatively small portion of the certified market, but they are still a big deal. They are not that hard to find, and they sometimes tell an interesting story. Here is a look at how many American’s buy their lumber in the self-service aisles of a major, do-it-yourself home center.

Below is a pile of ordinary dimension lumber in the home workshop of the MixedWood team – purchased from this very store last month. At a glance, this lumber is quite ordinary stuff, what we might call “run of the mill”. A closer look reveals some fun and interesting distinctions.

These boards are all spruce 2×4’s and 2×3’s. They are quite straight and true (premium studs) with lots of small knots. Take a close look at the end grain of the 2×3. Most of the boards look like this: a centered pith and closely spaced growth rings. And many have “wane” or bark-edges showing at their corners. These studs (measuring just 1.5 x 2.5 in. (38 x 64mm)) were cut from extraordinarily small trees. We counted about 45 growth rings in each. Where did these small, old trees come from?

CoC in action

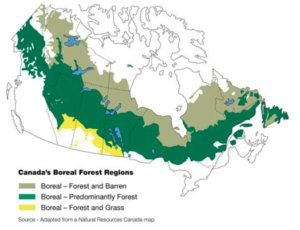

The answer – as you might have guessed – is not hard to find. It is stenciled right on the lumber! These are black spruce (Picea marinara) trees harvested in the Canadian Boreal Forest by a company called Rayonier Advanced Materials (RYAM). RYAM is an enormous company, made more enormous in 2017 by its acquisition of the Canadian forest product giant Tembec. Tembec is widely known as an early and loyal supporter of the FSC program and continues – under its current ownership – as one of the largest (4.2 MM ha) FSC-certified forest management companies in the world. Our lumber is traceable to a Chain of Custody (CoC) certificate managed by RYAM that includes a number of sawmills, and pulp & paper mills in Ontario and Quebec.

Can we be assured that the tiny, slow-growing spruce trees that were used to make our 2×3’s were grown, harvested, regenerated, and produced responsibly and sustainably? Not quite. But we do know that they came from a highly managed environment, with strict, independently verified, performance standards that stretch all the way from the forest to the lumber retailer. That’s a big deal and deserves some respect.

Complications

We can’t tell the story of Boreal Forest lumber, however, without mentioning the other side of the story. The very idea of commercial, industrial forest management in the Canadian north remains deeply controversial in some circles. The subject was raised again and featured prominently in news outlets across North American, when the NRDC published a white paper entitled “The Issue With Tissue”. It is interesting – and maybe an odd choice – that NRDC elected to emphasize the production & consumption of toilet paper (something we all use every day) rather than something like the lumber we write about here. But the issues are much the same. Is forest management in the Canadian Boreal Forest really the “wasteful and destructive practice” described by NRDC? We don’t know for sure, but we think that the answer is not so simple.

We can’t tell the story of Boreal Forest lumber, however, without mentioning the other side of the story. The very idea of commercial, industrial forest management in the Canadian north remains deeply controversial in some circles. The subject was raised again and featured prominently in news outlets across North American, when the NRDC published a white paper entitled “The Issue With Tissue”. It is interesting – and maybe an odd choice – that NRDC elected to emphasize the production & consumption of toilet paper (something we all use every day) rather than something like the lumber we write about here. But the issues are much the same. Is forest management in the Canadian Boreal Forest really the “wasteful and destructive practice” described by NRDC? We don’t know for sure, but we think that the answer is not so simple.

We are not going to try and tell the Canadian Boreal story here. It’s a long one and it’s far from over. Here are a few links for those who are interested: here, here, here.

An Interesting Comparison – and Some Questions

We like to visit the “big box” lumber retailers because of the amazing variety of wood products (certified and not) that they contain. The RYAM spruce studs are just one example. Before we finish this article, we’d like to share one more. This photo is of a “4×4” leftover from another project in the same home workshop. A quick glance tells us we’re looking at something very different – an interesting contrast to the black spruce studs.

We like to visit the “big box” lumber retailers because of the amazing variety of wood products (certified and not) that they contain. The RYAM spruce studs are just one example. Before we finish this article, we’d like to share one more. This photo is of a “4×4” leftover from another project in the same home workshop. A quick glance tells us we’re looking at something very different – an interesting contrast to the black spruce studs.

The 4×4 (measuring 3.5 in. or 89mm) is a piece of Southern Yellow Pine (SYP) – probably loblolly pine (Pinus eliotii). SYP is mostly grown in plantations the US Southeastern states; a region famous for its diverse forest products industry, reliant on low cost, highly productive raw material. Our piece of SYP is not labeled or (we think) certified in any way, so we can’t say anything further about where it was grown. The photo shows it side-by-side with a piece of boreal spruce 2×3.

The comparison between these two pieces of wood is interesting and worth thinking about. Both are cut from the center of a rather small tree. The pine tree was probably somewhat bigger than the spruce, but not very much bigger. It was much, much younger though – perhaps as little as 20 years from planting to harvest, compared with perhaps 50 years for the spruce. The comparison raises more questions than answers. Here are a few that we find interesting:

- Is it “better” (more ethical, sustainable, etc.) to grow trees quickly in southern plantations, than slowly in wild, northern forests? Is it worse? Why?

- Is it “better” to buy FSC-certified lumber from the vast, wild, intact, and precious Boreal Forest or uncertified lumber from an unidentified source somewhere between Virginia and Texas?

- Are small, slow-growing, 50-yr-old trees in the vast Canadian Boreal Forest “too good” to be harvested and converted into commodity wood products like lumber and paper?

- Is the significant investment made by RYAM in the FSC program an example of responsible corporate citizenship, or just a cynical attempt to “cover up” its exploitation of a precious global ecological treasure? Could it be both?

These are questions, not answers. Questions are complicated enough. Good answers should be even more complicated, don’t you agree? Please join the conversation. Do you have other, better questions? Or maybe some answers? Please let us know.