In my last post, I called attention to an important and interesting statement published late last week in the Newsroom section of the FSC-IC website. It is entitled “Towards a stronger FSC Chain of Custody.” In it, they provide us with several important and helpful updates; concerning the status of their Online Claims Platform, and a long-promised update to the Chain of Custody (CoC) standard. The central, underlying theme of the statement, however, reveals a serious flaw in logic that deserves more careful consideration. I call this flaw The Myth of the Gap.

Here are some excerpts (and highlights) which serve to illustrate the key points:

FSC International recognizes that there is a gap in the current FSC certification scheme – a gap with is present is all simlar Chain of Custody certification systems but which we wish to close.

The gap consists in the fact that the precise volumes … are not being compared between trading parties…current standards and processes … do not enable …certification bodies … to detect discrepancies…whether caused intentionally or through negligence. This makes it nearly impossible to detect this type of fraud.

Because we have evidence that this loophole is being used intentionally, we need to close the gap as quickly sand effectively as possible…

FSC’s position seems to be this: a serious, structural flaw or gap exists in the protocols of conventional CoC systems. Because of this gap, mis-applications of product claims are allowed to travel through the supply chain without challenge – posing an existential threat to the integrity of the FSC brand. This theory is – in my view – badly mistaken. To put it simply: there is no gap.

How CoC actually works

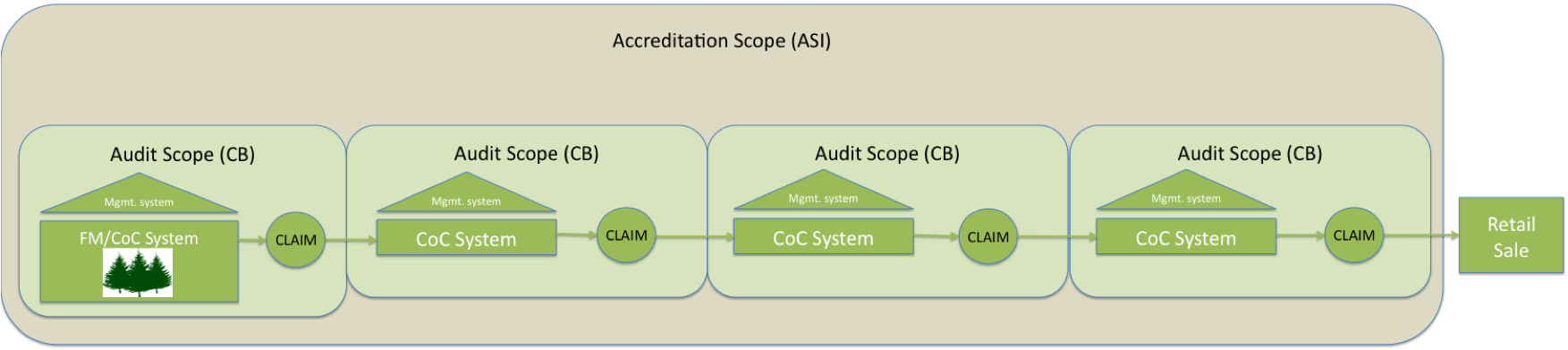

Earlier this year, MixedWood presented a series of articles on Chain of Custody (CoC). Part 1 of the series addressed what we call the “heart and soul” of what certified CoC is all about. We called our series “CoC SHOULD BE EASY” because, when considered conceptually, CoC systems are based on a few basic and straightforward business principals. The central concept is that – in a supply chain – products and materials always belong to someone. Take a look at the following diagram.

Here we have an stylized CoC supply chain. At the left, a Forest Management (FM) certificate provides raw materials (i.e. logs) from a certified forest. The certification of this forest is managed and verified by an independent and accredited Certification Body (CB). When the certified logs are introduced into the marketplace, they are identified, at the time of sale, with a formal statement – called a claim – which defines and documents their certified status. After the sale, they belong to someone else – the first “link” in the Chain of Custody (CoC).

When the first CoC company buys certified logs, they receive them with a certification claim, which they must verify according to the rules in the CoC standard. They process them according to one of the approved CoC system options (transfer, percentage, or credit). Then they assign their own claim statement to the goods that they produce (lumber, pulp, etc.). Each and every CoC company (without exception) has the responsibility of assigning a new claim statement to any product or material that they intend to be considered “certified”. The assignment of this claim falls within the scope of their CoC certification.

Every time that ownership of certified products change (i.e. purchase & sales transaction) a claim statement is required. Each and every claim statement falls within the scope of a CoC certificate, and is subject to audit by a CB. Eventually the supply chain is complete and a finished product is sold outside the CoC – often to a retailer. Until this point, however, certified products are always owned by certified companies. Each one has an CB, who are responsible to conduct regular audits to verify their conformance to the standard. Every transaction is audit-able and there is no gap.

Finally, the CB’s are subject to yet another level of verification. All are required to have an accreditation contract with an Accrediting Body (AB). FSC accreditation is done by its affiliate called Accreditation Services International (ASI). The AB – in effect – audits the auditors.

Does no gap mean no mistakes & no fraud?

Of course not. The great strength of FSC and its counterpart certification programs is that they function within the commercial marketplace. This fact gives our programs their extensive reach and influence. Market-based commerce is a powerful medium for effecting environmental & social change. It is also difficult, confusing, and often impossible to control. The existence of some fraud and mis-application is undeniable, and probably also unavoidable. It is a challenge we need to address. It is not, however, a gap to be closed, or a loophole to be eliminated.

Proponents of the myth of the gap are fond of describing a scenario like this: a certified company (in error or by design) applies a certification claim to a product that – for some reason – should not be certified. Once the sale is complete, that product is indistinguishable from other, legitimately certified products. This situation clearly occurs. It is a mistake, however, to understand it as a fundamental flaw in the overall system. By definition, the original, mis-applied claim must have occurred within the scope of someone’s certified system. The transaction falls within the scope of an audit, and (if the audit was effective) should have been caught and corrected. The answer, then, lies in supporting and protecting the existing framework of credible, rigorous, and independent certification auditing.

Some practical solutions

It is clear that the answer to reducing error and fraud in the CoC marketplace does not lie in the creation and maintenance of an enormous, central transaction database. Nor does it lie in new, costly requirements for well-intentioned companies to verify outside the scope of their own system. It is not sufficient, however, (or fair) to find fault with FSC’s proposed solutions without proposing some alternatives. Fortunately, we have some simple, practical, and effective options available. Here are two that should be considered:

Risk-based Verification. It is widely understood among practitioners, that CoC errors (& opportunities for fraud) are more likely in particular business sectors and regions, and to affect specific elements in the standard. Current accreditation protocols, however, make it extremely difficult for CB’s to apply this knowledge in their auditing services. CB’s should be freed, and perhaps even required, to apply their extensive knowledge to designing auditing protocols that focus audit effort where errors and mis-applications are most likely to occur. This solution could be implemented immediately, at no net cost to the marketplace. It is almost certainly the most effective option for improving and supporting the integrity of the FSC brand.

Standard Simplification. FSC is expected to release an updated version of its key CoC standard (FSC-STD-40-004) very soon. It is widely expected that the new version will be longer, and more complex than the existing one. This will be a mistake. The simplest, common application of current CoC standard requires (by my count) the verification of 53 specific indicators of conformance. Complex applications might require almost twice that number. As a practical matter, the current protocols require that CoC auditors record specific evidence to demonstrate conformance for each and every one of these indicators at each audit visit. This guarantees that they spend far too much time writing long, useless reports; and far too little time checking and verifying transactions and process controls. All this could be changed if the new standard is streamlined, and key indicators given proper emphasis. This would allow appropriate and effective attention to be applied where the actual risk of mis-application is.

Toward a stronger CoC

FSC is faced with some important, pressing, and challenging choices. If it is truly going to evolve into a program that is “simpler and more meaningful” some difficult changes in strategy and culture are needed. Above all, the relentless march towards more and more complexity and cost must be reversed.

The good news is that Chain of Custody can, indeed, be simple. By listening to each other, and having faith in consensus, we can prevent CoC from turning into an unsupportable burden; and ensure that it remains a value-adding asset to the wood products marketplace.